|

| Yet another lake by a mountain in Switzerland |

This blog post is part of a (nearly) yearly series on running a research group in academia. This post summarizes years 10 and 11, the first 2 years after moving to ETH Zurich. It also marks the end of the first decade as a research group leader, which is meaningful only because we have ten fingers and use 10 as a base for counting but I digress. There has been a lot to adapt to in moving to a new country including all the basics of moving, re-building the group and starting teaching. It was a lot easier than the first time around since I didn't have to set up the group from zero. Some people came with me, some stayed at EMBL-EBI with funding that couldn't be moved and generally speaking we could continue several computational related projects without much interruption. If we were primarily lab based then I think the interruption would have been more dramatic. Unexpectedly, there were more periods of high stress than I typically have. There was no particular reason for the stress but just a combination of multiple small things and probably due mostly to the adaptation to a new place. I will cover here some of the biggest things I am having to adapt to and also some of the research directions planned for the first 5 years of the group at ETH. One aspect that I will not cover is networking and getting to know the Swiss research landscape, but I will come to it in a later post.

The Swiss style of leadership

The EMBL, where I was before, has a very top-down leadership. EMBL is funded by different counties that are represented in the EMBL council. There is a director general who is appointed by the council and has a lot of control. Of course, there is a hierarchical support structure with a senior management team, heads of research units and a group of "senior scientists" that support the director in decision making. I am still figuring out ETH but there is a very different feel to it, both in size and style of leadership. EMBL employs around 2000 people while ETH has around 12,000. Organizationally, ETH is divided into 16 departments, and each department is further split into different institutes. For example, I am in the Department of Biology, which has 6 institutes, and I am in the Institute of Molecular Systems Biology (IMSB). As leadership, there is an executive board, including the president of ETH, then the Department heads, and in each department there is the meeting of heads of institute and the professorial conferences (i.e. all votes from professors). At least in the Department of Biology the heads of the institutes and the leadership of the Department are meant to rotate every 2 years. At these levels - institute and department - the leadership feels highly representative with lots and lots (!) of voting. This representative rotational leadership feels very different from EMBL and I think mirrors more broadly a Swiss way of doing things. The obvious consequence of this is that any change requires deep consensus and therefore radical change is less likely but it is too early to say much more.

Teaching at undergraduate level

During 9 years at EMBL I had almost zero teaching duties. I voluntarily taught some classes in the GABBA PhD program in Portugal and not much more. At ETH teaching is now an important part of my job. I am teaching courses in Bioinformatics and Systems Biology, primarily to biology students, which are all very familiar topics and close to my area of research. I don't particularly enjoy the act of teaching, in particular standing in front of 70-100 students and trying to explain things. As an introvert I am more comfortable with 1-on-1 or small group discussions and I get very tired with the interaction of teaching in a classroom setting. I have always said that Biology students should learn more computational skills so at least I have the opportunity now to influence that at ETH. In fact, the biology curriculum was changed right when I was joining to add more bioinformatics and they do have the chance to learn it with multiple lectures that cover bioinformatics and machine learning. Despite it being a mixed bag for me I am privileged in that I have a very low teaching load in topics that I like. Teaching is an area that I feel I could do more for and it could have an impact, in particular if we made it open to anyone. However, it is still something that I find difficult to fully devote to given the research role.

Our research at ETH during the first 5 years

The start of the research group at ETH has been fantastic. There was another big turnover of the group members during the transition, the second major turnover since the group started 11 years ago. I am really happy with the team we have here and having done this sort of turnover before, I can already see the growing potential of many projects that have started here. So the next 2-3 years is going to be about building up these projects and trying to coordinate them such that they interact and feed off each other. We have very generous stable funding as all other tenured prof positions at ETH - so called endowed professorships in the US or positions with core funding for the European researchers. Surprisingly, there is not a lot of oversight on this research funding which is a big difference from EMBL where the units, and their group leaders, are reviewed every 4 years. So I thought I could at least write down our commitment for research over the first 5 years here, in the spirit of disclosing what we are doing with this public research funding.

Human genetics research - mechanisms linking genotype to phenotype

Human genetics is an area that we started working on in the last 3-4 years or so of EMBL. Some of these things are already visible in recently published articles, including some protein-interaction network-based analyses of trait-associated genes. We continue to actively work on this and one direction of focus is to try to build interaction networks that are specific to different tissues or cell types. We are working on a manuscript on this and it is an area to continue to build upon, to be able to study the differences in cell biology of different cells/tissues and how genetic changes manifest differently in these. A second direction of focus here is to study the relation between common and rare variants linked to related traits using networks.

From cells to proteins - we are finishing a project where we are using protein structures to annotate functional residues in proteins to study mechanisms of pathogenicity. One aspect of this that will need further development is expanding on the prediction of structural modelling of protein interactions with other proteins and other molecules. Finally, we are interested in how genetic variation controls protein levels and ideally how to build computational models that can integrate the impact of genetic variation through control of protein levels, interactions, organs and organismal traits, ideally without a black-box modelling approach. All of these things are actively ongoing and I expect to have progress to report in the coming years.

Post-translational regulation - large scale studies of kinase signalling

There are over 100,000 phophosphosites discovered in human proteins and over 20,000 found in budding yeast proteins. We don't have good methods to study the functional role of these phosphosites nor to reconstruct the kinase/phosphatase-substrate signalling network of different cells. About half of the group is continuing to work on these problems and here at ETH we managed to consolidate the computational and experimental parts of our group which used to run in different locations while I was at EMBL. Because we are doing more of the experimental work now, this part of the group had a slower start but things are now moving along very well. Some of the problems that we are working on include the prediction of the biological process regulated by phosphosites; studying the impact of phosphorylation on protein conformational change; experimental methods to map kinase-substrate interactions and large scale mutational studies of PTMs. The thought has crossed my mind to phased-down a bit this area of research, or at least to move more into mammalian systems in our experimental work to make it more complementary to the human genetics side of the lab.

Structural bioinformatics, protein evolution and other

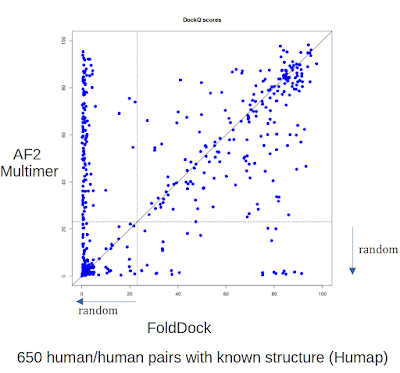

We have been having a lot of fun with AlphaFold2 ! With the current fast pace of change in protein related bioinformatics methods I am sure we will continue to play with these methods as they come. It is not likely that we will do a lot of method development ourselves, it is not our way, but I think we are very good partners for method developers to help make the bridge to applications. Protein structures, protein design and evolution models are all things we will likely be playing around with in the coming years.